International award-winning ice sculptor, Robert Neyland, offers his perspective on the carving of one of the world’s most famous monuments: The Great Sphinx of Egypt.

CARVE Like an Egyptian!

Posted 4 May 2020

It was still dark as we loaded onto the bus at the Mena House. To the east, the first hints of dawn were gathering to challenge the city glow of Cairo’s nighttime sky.

We needed to get moving–dawn would come quickly. We had a date for a specially arranged dawn visit with the Great Sphinx in the actual Sphinx Enclosure. Just us. We chugged up the hill and disembarked as the light gathered. The peak of the Great Pyramid began to glow pink. It was a wonderful 68 degrees.

We crossed the wooden boardwalk, down a wide promenade of stairs and there we were, standing at the feet of the oldest and most enigmatic statue on earth.

It was a curious Deja vu for me. I had studied the Sphinx for years; its distant gaze is what had drawn me to Egypt. In the two months prior I had observed it, I sketched it, and I sculpted it. Eerily, I felt as if I remembered every inch and contour of its gnarled and weathered body. This was a magical encounter, yet as we departed, I could not escape the feeling that we were leaving a crime scene.

For you see, the Great Sphinx of Giza is the victim of the most profound and enduring Identity Theft literally in recorded history!

The common belief is that a Fourth Dynasty Pharaoh had the Great Sphinx carved into the bedrock of the Giza Plateau in approximately 2,500 BCE. However, a rising tide of research indicates that the statue was already ancient when the King carved his likeness into the head 4,500 years ago.

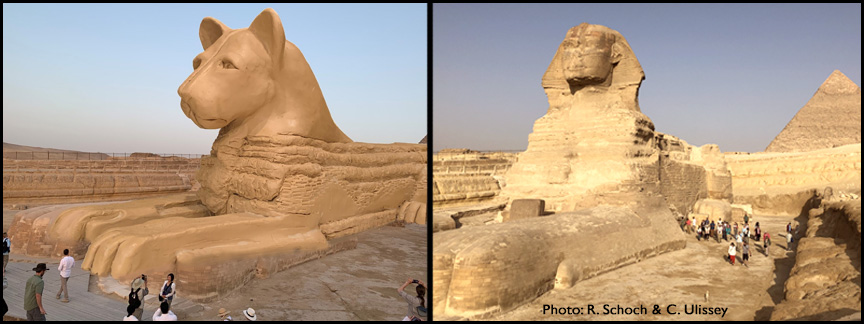

She was a lioness, facing east and guarding the horizon, as she had done for untold thousands of years. Her name was Mehit. The head of the Great Sphinx was re-carved during Egyptian times in the likeness of the King…which is also why it is too small for the body, and why it is curiously less weathered than the body, even though the head has been exposed for the entire lifetime of the monument.

We had the fortune to spend two weeks along the Nile during the ORACUL May 2019 Tour of Egypt. Prior to our arrival I had been busily sculpting a re-creation of the Sphinx to confirm if the modern-day visage could be derived from a lioness head.

When working in stone you can’t add it back on. That means if it is true that the head was re-carved, and that the statue was previously a lioness, then every aspect of the Sphinx head seen throughout its history must be able to have been carved into (or contained within the shape and volume) of a proportional lioness head and neck. This includes parts no longer existing; the Royal Nemes headdress with its characteristic breast lappets and ceremonial tail, and braided beard. (And a nose!)

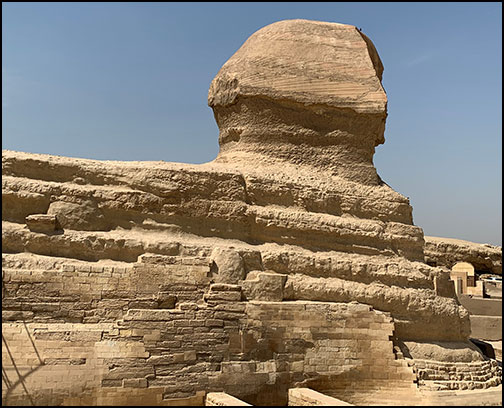

There is an important distinction to note. The Great Sphinx was quarried from the existing bedrock layers, NOT built. Even though the present-day monument appears constructed from layers of limestone blocks, that is the many, many series of repairs performed on the ancient statue over the last 4,500 years.

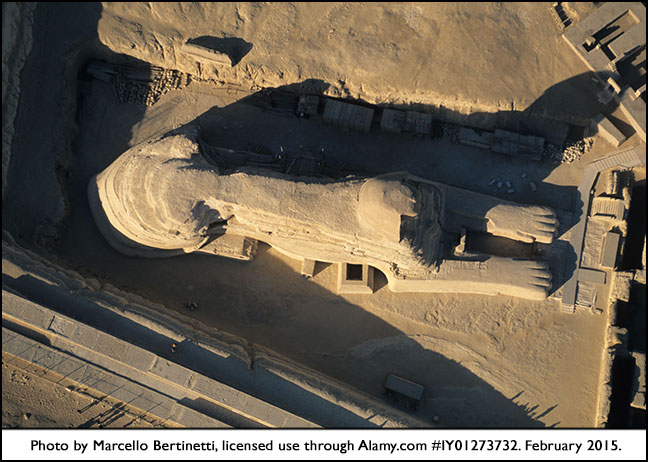

The Sphinx sits in the Sphinx Enclosure which was created when the stone was carefully quarried away from around it, revealing the statue as one solid piece of layered limestone. Except for the promontory that made up the head, the entire statue was carved down into the bedrock of the Giza Plateau.

Quarried with incredible precision, the stone was removed in colossal multi-ton blocks and moved, shaped, and used in building the adjacent Sphinx Temple and Valley Temple.

The Sphinx’s head we know today does not look like it did in ancient times. Breakage scars behind, under, and in front of the head indicate the presence of former elements which have eroded, broken, or been vandalized over the millennia.

The historical record suggests that the Great Sphinx was one of the first images of a royal coifed human head on a lion body. Certainly there are thousands of years of sphinx imagery throughout Egypt, but they all date after the “official” creation date of the Great Sphinx. It was not even called a sphinx for 2,000 years when the name was applied by the Greeks! However, lioness, lion goddess, and recumbent lion imagery appears everywhere, dating back to predynastic times.

What telltale signatures remain today? Did the historical Sphinx have a beard? Ceremonial tail and breast lappets? It would seem so…Fragments of a long, braided beard attributed to the Great Sphinx were found at the base of the chest in 1817, the earliest recorded modern excavation of the Sphinx.

It is quite possible there was a tail structure behind the head of the Sphinx, and there is a significant telltale breakage scar at the rear of the head, right in line with a fissure that transects the monument.

What about the characteristic breast lappets of the Nemes headdress? There are a few protruding nubs of original bedrock on the neck and shoulders that compellingly suggest the lappets were present and therefore they also had to be incorporated into the reconstructed model.

Sculpturally, the concept was simple:

Recreate the Sphinx as it appears today, then work backwards adding the missing presumed historical features. Sculpt the lioness head, and then slice the head in half, hollow it out, and install the head pieces like a clamshell over the Sphinx head and examine the fit.

The key element was the front to rear placement of the proposed lioness neck onto the body and its orientation. For example, if the lioness head was stretched too far forward, the resulting neck would not provide the needed volume to contain the present-day head.

Deep into this sculptural process, with both eyes on a display of several Sphinx photos, I let sculptor’s fingers seek the appropriate location on the body. Holding the lioness head and hovering over the model, my fingers found the landing spot that seemed proportionally correct, balanced between front of chest, front elbows, and rear paws.

Then something astonishing happened. I looked back at the online images, and the one crisp, clear 2015 aerial photo I had found. Illuminated in the long sunset light was a silhouetted hump right behind the head, exactly in the shape and location I had just identified on the reconstructed model.

What the HECK? The hair stood up on my neck, all the way down my arms. What just happened?

Visible from the air and in just the right light conditions, this faint stone outline appeared to be in the precise location, aspect, and shape that a previous lioness neck might have.

I wrote a paper on this subject which was published in the January 2020 issue of Archaeological Discovery. That hump is a specific limestone layer of the Sphinx head and neck.

It is not clear whether this thin eroded boundary layer between the Sphinx body and neck is the product of natural erosion or is a remnant signature of a prior sculptured element. However, with the proper exposure sensitive markers, it should be possible to test this prediction. This could indicate if the hypothesized neck area was exposed as a surface more recently (circa 2,500 BCE when it was re-carved and the old neck removed) compared to the adjacent stone surface of the back and rump area, which should be far older. In theory, this differential may be as much as seven thousand years.

History is like a crime scene; once you acknowledge that an event may have occurred, the footprints and forensics are everywhere. All across the globe, and all across the centuries are footprints of a prior cycle of Civilization that perished in the cataclysmic end of the last ice age. They are hiding in plain sight, waiting to be understood.

– – – – – – – –

Special thanks to Dr. Robert Schoch, Catherine Ulissey, Dr. Manu Seyfzadeh, Mohamed Ibrahim, and the late John Anthony West for their research and inspiration.

View my technical journal paper, upon which this article is based, in Archaeological Discovery at: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/AD_2019110616005106.pdf

For the 2017 paper by M. Seyfzadeh, R. Schoch, and Robert Bauval establishing the identity of the original Sphinx as the lioness Mehit, see: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/AD_2017072615041268.pdf

About the Author

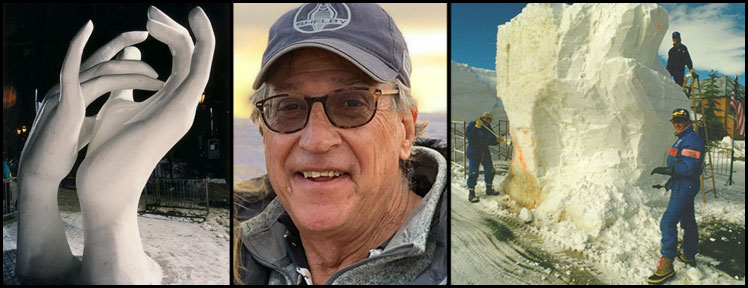

Robert Neyland is an independent researcher from Breckenridge Colorado. Over the past 30 years, he has competed around the world as part of the United States Snow Sculpture Team, winning numerous Gold and Silver medals in international competition in Finland, Moscow, Sapporo (Japan), and Breckenridge (Colorado). These international competitions involve rendering a dense and brittle 25-ton frozen block into a finished sculpture in four days using only hand tools. “You carve away everything that doesn’t belong, and there’s your sculpture!”

All photos in this article are courtesy of R. Neyland, unless otherwise indicated.

Back to Top – or – Back to Presentations

Disclaimer: Articles published on the ORACUL website are the responsibility of the individual authors, including but not limited to factual reporting; permissions and copyright issues regarding the use of images and quotations; avoiding libelous statements; and so forth. Authors of articles are expressing their own personal opinions and do not speak for nor represent ORACUL. Neither ORACUL as an organization, nor any members of the Board of Directors, Advisors, Staff, or any other persons associated with ORACUL, in their capacity as ORACUL officers or in association with ORACUL, endorse the content of any articles published in this section of the ORACUL website.